At other times1, we said that the term nahualli is a Nahuatl word whose meaning remains unknown seems to be close to the notions of “coverage” or “disguise”2. As you know, that term can also designate a kind of witch-change (sometimes called man-nahualli) is often applied to a kind of alter ego or double, usually animal, which is so closely linked to the personal identity that all evil that affects the nahualli will affect their human counterparts. So that the damage suffered by the double will constitute one of the possible explanations for the disease. According to what is found in ancient sources, the shape of nahualli varied because of the distinctive features of the character he was associated3, may in some cases, serve as a name4.

However, this does not imply that the doubles are unique to humans because, apart from the gods, we find cases in which a same-nahualli or nahualli kind is attributed to a community5. At the same time, we have ancient testimony that appeared to indicate that some privileged people could be linked to more than one double6. As shown in various ancient and colonial sources, the nahualli was also the form adapted by the ritual specialist, also called nahualli or man-nahualli, during the transformation process. So, the diversity of forms adopted by that character could be explained in terms of the multiplicity of double associated with a single individual7.

After this brief summary of ancient beliefs about nahualli, one wonders if a concept as complex and important to the Mesoamerican worldview could not have been equally reflected in the visual manifestations of pre-Hispanic times. If such records could not give additional information on the nahualism and, if the first question is affirmative, how it could have been embodied the notion of nahualli. Thus, the main intention of this work will be how plastics arts represent the nahualli between the Aztecs and other pre-Hispanic cultures.

Representing the nahualli

Among the many definitions that can be found in the word representation, one element that seems to remain constant is the idea that representation involves replacing a missing element in this element, the object represented by the representative object (signified/signifier ), is an image, an act, a tactile signal or even a smell. This simple operation, which forms the basis of human communication8 , stems from a sort of “convention” on the elements that serve to replace the objects represented, so that all people who know the conventions will be able to understand the meanings expressed. To allow communication, there must be an issuer, in this case the person or group that generates the image or sculpture, -a way to spread the message- and a receiver who knows the conventions and is able to understand the message.

So in order to define the way the nahualli was represented by the image, we must discover the conventions that allow the transmission of such a concept by other means than spoken language. This will need to start by the inverse of significance, ie decoding: seeing how the nahualli was meant, where we know beforehand that this is the nanahualtin of a certain character, and then try to deduce the convention that would allow their identification in unknown cases.

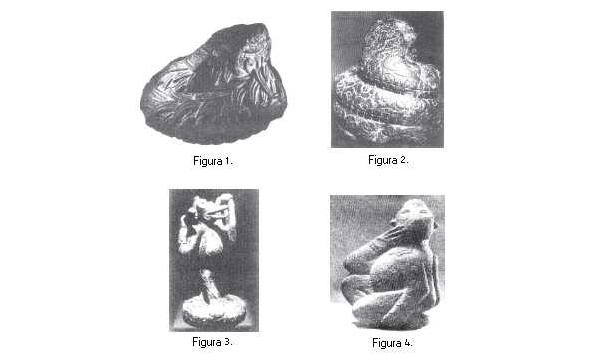

To this end, it was decided to consider only constructions in which the character is associated with its nahualli, because in most cases be impossible to distinguish a double-nahualli of a simple animal when it is isolated. The only known exceptions would be those images that carry the name, sign of the tonally9, or other symbol or character linked to the studied character. Such exceptional cases, we can cite the sculptures of the feathered serpent, preserved in the Musée de l’Homme and the National Museum of Anthropology (Fig. 1) – which, bearing the sign “1 cane” on the nape, are linked to Quetzalcoatl. The sculpture of a serpent with jaguar spotts-preserved in the Museum für Völkerkunde Stoatliche Berlin (Fig. 2) – who, taking a smoking mirror in the same place can be considered as nahualli of Tezcatlipoca. Finally, the monkey statues –of the Musée de l’Homme and the National Museum of Anthropology (Fig. 3 and 4) – that by carrying cut snails on their chests and an Ehecatl mouth mask are associated with Quetzalcoatl.

Also, it was not possible to find the indicators that would allow to identify the men – nahualli, in absence of their doubles, in the field of the image. The only located representations are those of the Florentine Codex10 that do not show any specific feature that leads us to distinguish them (fig. 5 and 6), and that one of the Title of Yax (1989)11 who presents us a statuette of a warrior carrying a bow next to a little flag (fig. 7).

The representations of the nahualli

The first thing we see in studying the representations of nanahualtin is that there is no rigid rule to determine the manner in which such entity is to be signified, but rather a series of conventions, more or less relaxed, on the way the different elements can combine to produce the same meaning. That is, instead of having rules, the construction of the images seems to be variable within the limits of recognition. That could be identified four main types of representation, which also can include some variations12 .

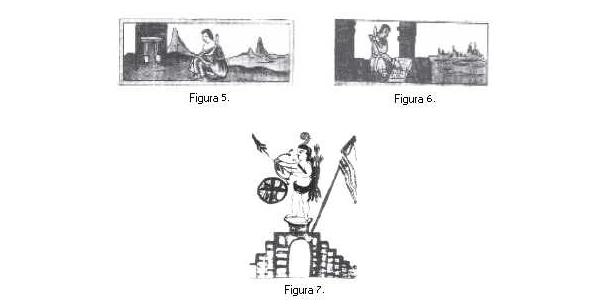

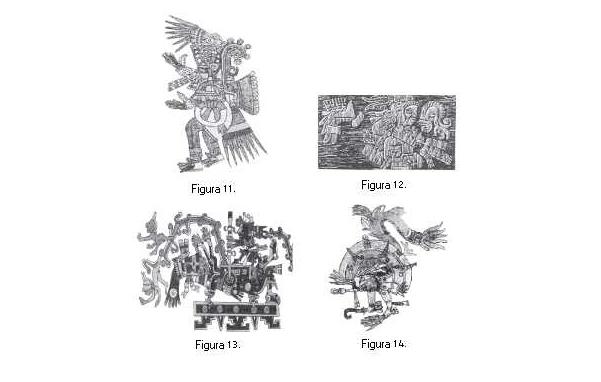

Type a. This group consists of all those figures, as set out Sahagun’s13 informants on Yxcozauhqui and Huitzilopochtli, carry their nanahualtin on his back14. Such is the case of a green stone statue of bergische Wurttem Landesmuseum in Stuttgart, which represents Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli carrying on his back the feathered serpent, nahualli of Quetzalcoatl – and consequently of Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli , with the solar disk. At the top of the figure, the head of the animal anthropomorphic figure touch (Fig. 8).

Within this group, there is a variant in which the nahualli is represented by its head or its tail, located on the back of the character. These would be the cases of the Huitzilopochtli and Xiuhtecuhtli images that appear in the Florentine Codex15 (Fig. 9 and 10)

or the image of Huitzilopochtli as contained in the Codex Borbonicus16 (Fig. 11). This could also be the case of a petroglyph of the Hackmack box in the Hamburg Museum fur Volkerkunde und Vorgeschichte, on which we see Motecuhzoma, recognizable by his name glyph, piercing his ear and wearing a jaguar head on his shoulders (fig . 12).

Type b. The second type is one in which the characters seem to emerge from their nanahualtin. Such is the case of the Xiuhtecuhtli image, that emerges from the torso to the snout of a serpent of fire on which a priest lights a flame in the Codex Borgia17 (Fig. 13) and that of Quetzalcoatl, emerging from a Solar circle completed in plumed serpent’s tail in the Codex Vaticanus18 A (Fig. 14).

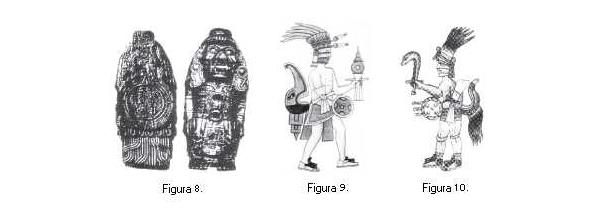

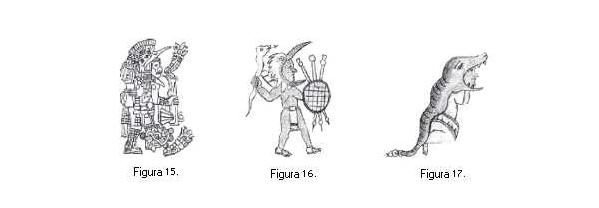

However, the more frequent and more used form used by the ancient sources, is the one showing the head of a character coming out of the snout of the nahualli. Thus, the Florentine Codex19 says about the image of Coyotl inahual that “she is endowed with a coyote head showing what looks like the face of a man.” Later, the same text20 says, similarly, “Macuil Ocelotl was carrying the head of a beast form which his face was coming out […] and just as Macuil tochtli also carried his nahualli as a rabbit’s head.21 A similar presentation is discussed22 in connection with the amaranth sculpture of Huitzilopochtli “and around his head was his nahualli hummingbird”23 , as contained in the Holy War Teocalli (Fig. 15) or in the Codex Azcatitlan24 ( Fig. 16). This type of construction appears most frequently in the codices.

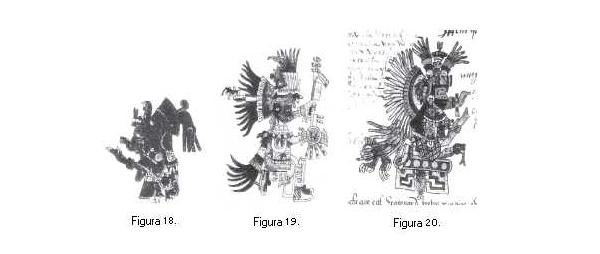

We note, for example, in the Codex Azcatitlan (1995, 10v)25, a representation of Cihuacoatl (women snake-female serpent) who kneels with a snake on the back that opens the mouth to let out the face of the deity (fig. 17). Chalchiuhtlicue, in the Codex Borgia26

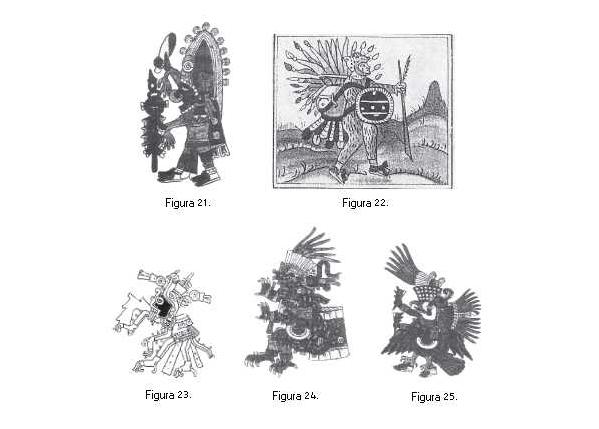

carries a kind of headdress shaped like a serpent with open jaws (Fig. 18). Tezcatlipoca and Xochiquetzal are wearing a kind of helmet-shaped with the head of a bird, probably a quetzal bird in the case of the goddess, in the Codex Telleriano Remensis27 (Fig. 19, 20). Or Xiuhtecuhtli, which appears in the same codex28 with a fiery serpent’s head with open mouth on one side of his face29.

Sometimes what is called nahualli is presented as a sort of dress or costume, an example of this would be the Macuil ocelotl image that appears in the Florentine Codex30 , in which we can observe the shoes and hands emerging from the jaguar skin (Fig. 22). A similar example would be the image of Tlaloc dressed as an alligator contained in the Codex Borgia31 (Fig. 23) and Tezcatlipoca wearing a jaguar and turkey suit in the Codex Borbonicus32 (Figs. 24 and 25).

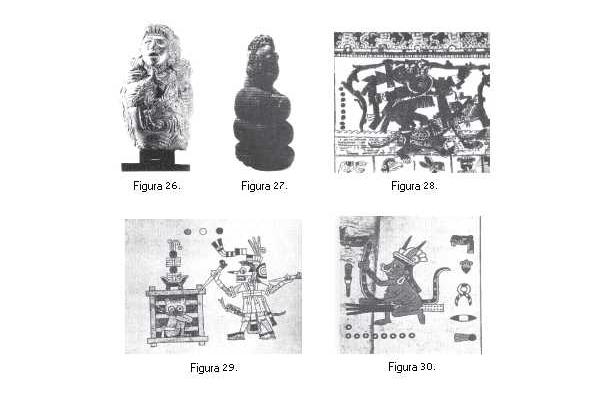

It is possible that the sculptures of characters that emerge from the snout of feathered serpents or snakes, knotted, vertical or rolled-as preserved in the Musée de l’Homme and the Museo Nacional de Antropología, correspond to the same type of representation (Fig. 26 and 27)33 .

Type c.The third type, one of the best illustrated, consists of those images in which the figure of nahualli lies behind the character. An image of the Codex Vaticanus B34 shows a representation of a monster-cipactli profile placed behind Tlaloc and facing the same direction as the deity (Fig. 28).

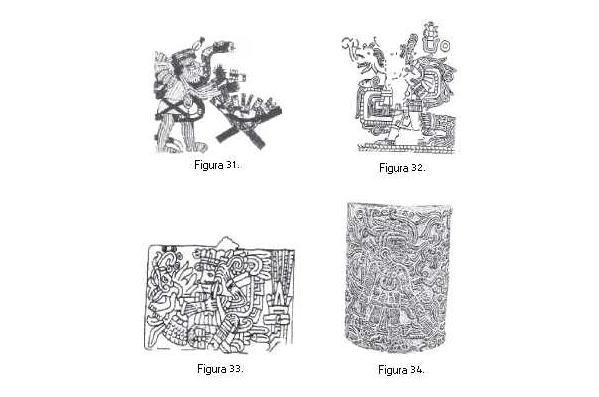

Mictlantecuhtli appears with a small snake on the back in the Codex Laud35 (Fig. 29) in that it observes a Cihuateteo with a similar snake behind him in the Codex Laud, Fejer-Mayer and Vaticanus B (Fig. 30, 31 )36.

In a relief of Cerro de la Malinche, Tula, Quetzalcoatl can be seen recognizable by his glyph, standing in profile on a petate (a mat) piercing his earlobe. Behind him, on the side of 1 Caña-glyph -calendar name and tonally-sign of Quetzalcoatl-, is an enormous feathered snake with stone knives and it’s head facing the same direction as the main character (Fig. 32).

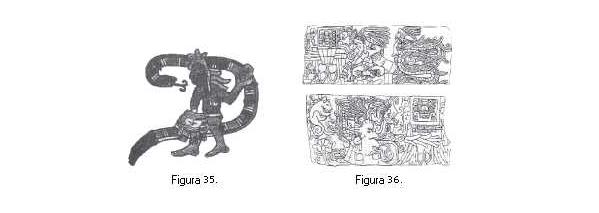

A similar construction occurs in one side of the box of General Riva Palacio, which shows a person seating and piercing his ear and a fiery snake behind him (Fig. 33). In one of the twin urns of the Templo Mayor, a snake with knives was engraved behind Mixcoatl and a feathered snake behind Tezcatlipoca (Fig. 34). The Codex Borbonicus37 presents the image of a multicolored snake that undulates at the back of an anonymous character in an attitude of self-sacrifice (Fig. 35). On the Acuecuexatl stone is a feathered snake behind a seated figure, identified as King Ahuizotl, for the glyph of the mythical animal’s name that is the same as his name, piercing his ear, below

a date 7 caña marked on a small base38 . The back of the stone shows a layout similar to the previous one, except that the feathered snake is on one side and the base has no signs of water. However, the fact that the second feathered serpent appears beside the character and not behind, could simply be, as noted by Graulich39 , effect of splitting of an element that should be located behind the character (Fig. 36). Thus, if we consider the tlatoani representing the deity, the feathered serpent could be the nahualli of the King Ahuizotl considered representative of the sun. The feathered snake would than be “his double animal, the blue sky that goes with the sun.40

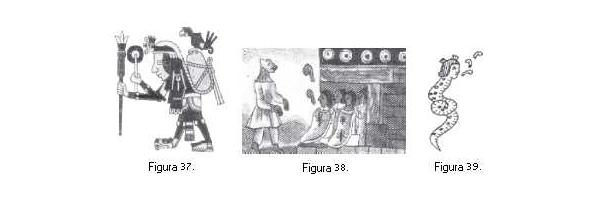

Type d. The characters that carry their nahualli-head instead of on their foot make the fourth type, the least frequent of all. Such is the case of the image of Huitzilopochtli that appears on the front of the holly war Teocalli with a fire snake instead of the extremity (Fig. 15). Similarly, the Codex Féjérvary Mayer41 shows the image of a merchant god, identified by Olivier42 as Acxomocuil, carrying a snake’s head instead of the foot (Fig. 37)43 .

However, it seams that these snakes replace the usual smoke rings listed on this site. In fact, it is possible that this type of representation is particularly associated with Tezcatlipoca, characterized by amputation of the foot-and their avatars.

There are other forms of representation that are used infrequently and therefore do not classify with a particular type. The nahualli can, for example, appear in front of or under the character they are associated with, like the feathered snake that appears before the image of Ehecatl and the fire serpent on which Xiuhtecuhtli sets fire with a stick in the Codex Laud.44 It is possible that the snake coiled around the neck of Tlaloc in the Codex Vaticanus B45 is also one of his doubles (Fig. 28). Another rare form of representation is one that involves the replacement of the head of the character for that of the nahualli. One example is the image of Coyotl inahual with a coyote head, which appears in the Florentine Codex46 (Fig. 38) or, in the same codex, that of Huitzilopochtli wearing the head of a bird. Finally, there are cases where the character’s head replaces that of the animal to which it is associated. Such is the case of the image of Cihuacoatl in the Florentino Codex47 (Fig. 39).

Representation, dress and transformation

Summarizing, we see that the four types of nahualli representation we have mentioned can be grouped into two major classes: first, the types of representation in which the double is simply associated with the character48 and, on the other, the representations in which the person carries the nahualli on himself49. The same nahualli can appear both associated to the character, as worn by him. In the Codex Borbonicus50, the fire snake appears on the back of Huitzilopochtli. In addition, the Codex Borgia51 shows the snake replacing the body of the deity and the anthropomorphic face emerging from the animal snout. The feathered snake, figure associated to Quetzalcoatl in the petroglyphs of La Malinche, and on the divinity in the sculpture at the Musée de l’Homme. The snake of fire appears associated to Xiuhtecuhtli in the Codex Florentino and carried by the god in the Codex Borgia. We could conclude that this second type of representation could be the fact of wearing the nahualli or a way of taking a different form.

In fact, it seems that in the pre-Hispanic times the nahualli was considered as a sort of dress or covering. This is particularly evident in the description that makes Tezozomoc52 of the funeral ceremony of King Tizoc: “Having done this, and having sung in front of him, they disarrange him again in order to adorn him with the dresses called Quetzalcoatl. And before they painted him with black smoke from the marmija, and instead of a crown they placed a wreath called Ozelocompilli and a different blanket they call nahualix”. It is possible that the action of the nonotzaleque53 to wear a jaguar skin is related to the transformation, since, as Sahagun’s54 informants say, this is a cover that provides its holder some of the qualities of the animal: It is said that with this, they move forward enduring the difficulties. It is said that this fills others with fear.”

If we review the vocabulary used by the ancient sources to express the idea of transformation, we can see that even if Molina translated from Castilian “transformarse en animal” as a ninio. mazatilia, nino. Tochtilia55 , the shape change is, in most cases, referred to throughout the verbs cuepa (nino)56 and nahualtia (nicno)57. The verb cuepa has a meaning similar to the verb “tornar” in Spanish, ie at the same time expressing the concepts of rotation and change.58 While, as we said, nahualtia means “to hide, disguise” or “cover with something.” Thus, if we consider that, as the Codex Florentino59, “transformation [man-nahualli] turn into its nahualli“, “transformed” is equivalent to “cover” with your nahualli.

In the stories of transformation of contemporary Mesoamerica, the allusions to matters of dress or change of skin are extremely frequent60 . In such stories the skin, feathers or the garments are in some way, the repository of the figure of the different beings. Indeed Báez-Jorge and Gómez Martinez61, mentioned that among the Nahuas of Chicontepec, the word “skin” is used to translate the notion of “costume”62 . With which we could confirm that, as noted Cordier, “the transformation to human (or conversely, from human to animal) essentially reduces to a matter of clothing.”63

Dissemination and representation of nahualli

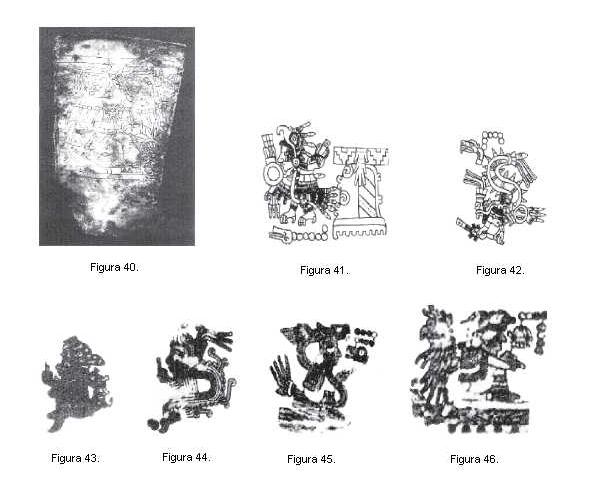

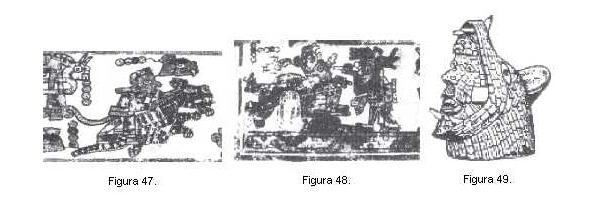

The types of representation of the aforementioned nahualli also appear in other regions of Mesoamerica. A pectoral made of shell in the Huasteca region, which shows a bearded figure dressed as a bird and with a feathered snake behind him, seems to group the types b and c (Fig. 40), while a stele of Tuxpan-preserved in the Museum für Völkerkunde Stoatliche Berlín shows a character with attributes of Quetzalcoatl, piercing the tongue, surrounded by a snake. In the Mixteca, the codices, such as Zouche Nuttall (Figs. 41 and 42), Vindobonensis

(Fig. 43 and 44) the Selden (A2) (Fig. 45) or the Bodley (Fig. 46 and 47)64 often represent characters emerging from the snout of an animal carrying the nahualli or the nahualli behind them.65

Nahua sources mention the existence of nahualli-man at Teotihuacan and the among the Olmecs uixtoti, “the first inhabitants of the region.”66 While the Mayan documents of Guatemala and Chiapas seem to place the origin of the nahualismo in the mythical city of Tula.67 Therefore, we should expect to find representations of nanahualtin, at least from the Early Post classic.68

The Florentino Codex69 states that the Toltecs “arrived at Tula, at Amatlan” which relate to the amatecos, of which one of the patron deities was Coyotl inahual, with the Toltecs. In fact, in Tula, Hidalgo, there was a sculpture showing the head of a coyote with open jaws and a human face emerging from them, as Sahagun’s informants described inahual Coyotl image (Fig. 49). In addition, there are images of characters wearing feathered serpents on their backs, which would be close to the type c of the classification suggested in this paper (Fig. 50). The Atlantes de Tula are wearing sandals decorated with feathered snakes, so it is a close image of the nahualli appearing instead of the foot. According to this, there must be a number of similar Aztec images showing different ways to represent the nahualli.

We find similar images to the type b-faces emerging from the snouts of animals- in Chichen-Itza and figures of warriors who wear feathered serpents on their backs (Figs. 51 and 52), which according to Lobjois70 would correspond to representations of nanahualtin

or the animal transformation of fearsome warriors. It is possible that in this case, the feathered serpent was seen as a collective nahualli –nahualli of the city or of some elite, or of a particular ethnic group or of the warriors in general-. Since, as seen on the facade of the Temple of the Warriors (Fig. 51), this animal appears repeatedly in association with groups of characters brought together in one scene. Therefore, it appears that nahualismo was also present among the Maya-Toltec early Postclassic.

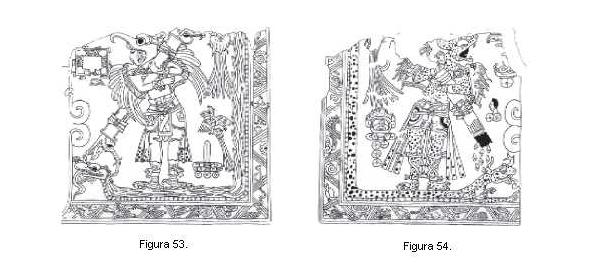

We also see quite explicit nanahualtin images at Cacaxtla, in a pretolteca period [around 750-800 a.d.] and in a style clearly influenced by the maya plastic from classical periods. The characters of Cacaxtla relate to nahualli animals around them – a Feathered Snake and a Snake-jaguar – skins and animal headdresses that they wear (figs. 53 and 54).71

Maya Nahualismo and other nahualismos in the Classic Period

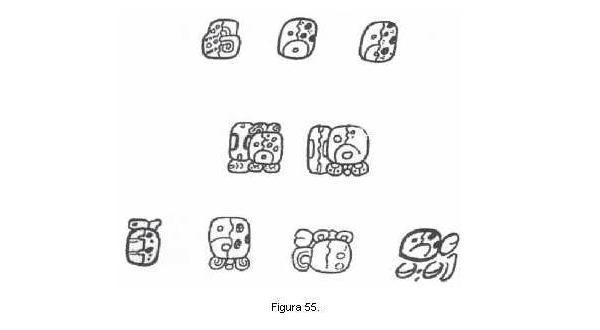

With regard to the representations of the Maya double-nahualli, the greatest contribution that has been made to the present day is undoubtedly the decoding of the glyph way (Maya equivalent to nahualli), by Houston and Stuart. According to Grube and

Nahm; Kettunen and Helmke, and Hoppan72, this glyph —known as T539 o T572— consists of a sign ajaw “Mister” partially covered by a jaguar skin (fig. 55). Houston and Stuart explain that:

In most cases, the affixes associated with the T539 and T572 are the phonetic symbols WA and YA. Typically, T539 appears before WA; YA appear later. In Palenque, a composition of glyphs containing T539 shows that WA is an optional prefix. WA and YA sometimes found together -WA-YA/T539 or T539/WA-YA- or missing. In our opinion, the most logical explanation is that the phonetic signs read as “way” are reading the glyph to which they are associated. Thus, we propose that T539 is a reading logogram whose “way” simply affixes function as phonetic complements.73

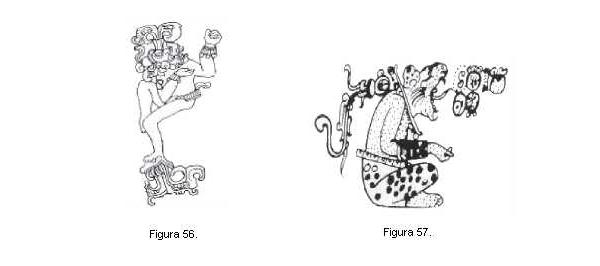

A few lines later, the same authors74 note that this glyph appears often as u-way, “the way of,” and present a series of glyphic texts that explain what kinds of way of diverse characters. One of the most interesting texts is that of Temple 11 at Copan, according to Houston and Stuart75, says, “His foot is the way of God K”. Considering that continually the leg of this deity ends with a snakehead (fig. 56), it would be an equivalent composition to the images of Tezcatlipoca, Acxomocuil and Huitzilopochtli.

Thanks to the inventory realized by Grube and Nahm — where we find a compilation of the occurrences of the glifo way in the Mayan vases76—, we could classify the iconic representations that are associated with this glyph into two major groups: a) representations of the way in the form of animals or fantastic beings not associated with characters. And b) representations of characters associated with their way-recognizable by their parts or the whole being. Obviously, the representations of the first group could not have been identified in the absence of that glyph.

However, among the images of the second group we found some items that tend to recur: 1) the characters have the head of the species-double superimposed on it six times. 2) In four cases, the way species is represented as a sort of dress-trousers, gloves or boots, carried by the characters. 3) In only one representation, the head of the animal replaces that of the human. (fig. 57) 4) On two occasions the character seems to emerge from the muzzle of the animal, shows the head or body to the waist. 5) In one image the way is around the character in a circle around him.(Fig. 61). This way then, we see that in their more general features the Mayan representations of the double do not seem to be far of the types identified for the Aztec nahualli. The characters that carry the head of their double on themselves remind us of the image of Chalchiuhtlicue from the Codex Borgia. The men who wear trousers and jaguar gloves are equivalent to the image of the Ocelotl Macuil from the Florentino Codex. Characters that emerge from the snout of their way are close to the type b of our classification, and so on.

Starting from a phonetic reading, Freidel, Schele and Parker77 proposed that the cartridge G1 lintel 25 of the structure 23 of Temple 11 at Copan should be read as “he was nawal”. This would imply that in the classical period, the nawal term was used in the Maya area and coexisted with the Mayan word for the notion of double. However, according to Sala78, these researchers have made the mistake of reading “or wala na bah il” “the nagual was his image” instead of “u bah na il ol” “was the image of the first entrance”.

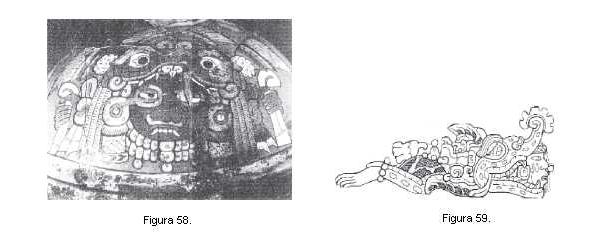

Furthermore, we also find representations of nanahualtin not associated with Glyph way. It is possible to see, for example, the image of a character with the eyes and fangs of Tlaloc, emerging from the mouth of a snake in a vase with top from the Museo de Tikal (fig. 58), and the representation of a human coming out of the snout of a reptile that appears in another engraved vase of the same site (Fig. 59). It is possible that the double of -or D-god-

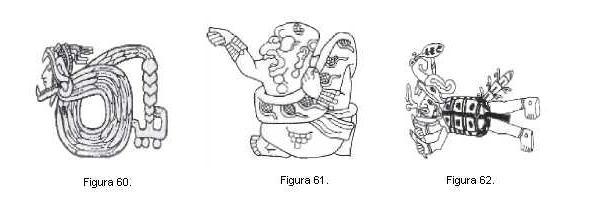

might be the lizard, because as in the representations of the classical period-like sculpture of Temple 22 and Altar at Copan-D appears a human face emerging from the muzzle of this animal. There is also the image of a character coming out of a feathered snake in one of the rings of the ball game of Old Chichen (Fig. 60), while the Copan Stele D features a character with snake features and a snake that wraps around his torso (Fig. 61).

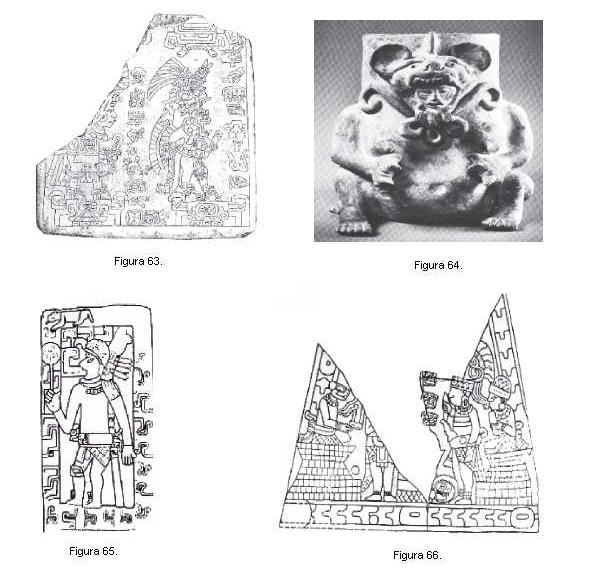

In other cultural contexts of the classical period nanahualtin images seem less explicit. We observe in Monte Alban, on the Tombstone of Bazan, the image of a Zapoteco man dressed as a jaguar, associated with a character identified by Marcus and Flannery79 as a priest of Teotihuacan (Fig. 63). An anthropomorphic figure dress in an equivalent manner appears in the painting of the north wall of the Tomb 5 on Cerro de la Campana. Similarly, in Zaachila appears the image of a human face emerging from the open mouth of a turtle (Fig. 62). Often in the mural paintings of the Zapoteca tombs appear characters wearing zoomorphic helmets, for example in the paintings on the walls of tombs 125, Monte Alban and 1 Huitzo. Finally, a Zapoteca urn of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin shows a man coming out of the open snout of a jaguar (Fig. 64). These examples seem to come at the type b of our classification of representations of nanahualtin.

The Tajín, Veracruz, features in the Workshop N the engraving of a man carrying a kind of helmet in the shape of the head of a bird (fig. 65), whereas the Sculpture 7 shows the image of an individual sitting down with a head of a rodent or a jaguar (fig. 66).

Found in Teotihuacan representations of humans dressed in animal skins, carrying a zoomorphic head of which rises the human face. These would be the cases of the so-called Butterfly God of Tetitla (Fig. 67), of a character dressed in Eagle found in Zone 5 (Fig. 68) or a relief in Teotihuacan style in the region of Soyoltepec, showing an individual wearing a helmet shaped with a snakehead (Fig. 69). However, such images are not conclusive, since the fact that a character is dressed in animal does not necessarily imply that this animal is his nahualli.

It could be a simple military insignia similar to the costumes of the eagle and jaguar warriors of the Aztec culture.80

Nahualismo in the Preclassic

In Olmec sculpture (1500-300 BC), we observe quite frequently anthropomorphic representations with animal attributes. In many cases, they are asexual characters with feline features. In addition, there are figures composed with characteristics of several species, and others that combine the features of different animal kinds. Obviously, between the multiple and varied explanations of such sculptures we find some that try to associate them with early manifestations of the nahualismo.81

Taking as a starting point four asexual and anthropomorphic statuettes with feline features82, Furst created an entire theory of shamanism and belief in the transformation of the Olmecs.83 The author points out-correctly-that actually Olmec representations of jaguars, in whole zoomorphic, are quite rare and that, conversely, are humans with jaguar features that appear more frequently. This physical type is opposed to that of the colossal heads and Mongoloid style of most of the completely anthropomorphic figures. This means, according to the author that the problem lies in the interface between the human and jaguar and not the jaguar symbolism itself.

Then he makes a brief description of the South American beliefs associating men and jaguars. And notes the constant association of the jaguar to the souls of the Native American ritual specialists. He also indicates the existence of a qualitative identification between the figure of the shaman and the jaguar, which can be, according to Furst, interchangeable. He quotes a number of historical stories and ethnological descriptions that mention transformations of the shamans into jaguar in altered states of consciousness. He also indicates that the faces of the jaguar-men have a sort of grimace that denotes a severe torment or a state of ecstasy84, and concludes that, given the age of drug use in America, the jaguar-men statues should represent the ecstatic experience -thus real-lived- of the transformation into a jaguar. Finally, Furst chooses some ethnographic and historical examples to show the relative importance of the jaguar in the Middle American nahualismo and suggests that this system of credence can be understood as a local declaration of the American Indian chamanismo85.

To start with, it is necessary to point out that the majority of the objects studied by the author come from the plundering and, consequently, they lack the necessary archaeological context to establish their use and significance. Late historical sources or ethnographic Mesoamerican, which I believe would be closer to the Olmec beliefs that the South American ethnographic data are not used for the approach of the hypothesis. When he uses ethnographic data, does it completely out of context, without taking into account the set of beliefs that occur about shamanism. And not to mention the differences between the beliefs of the groups he mentions. Furthermore, the corpus of representations studied is too small. Above all, does not take into account children’s representations with jaguar features, which could hardly be related to shamanism. Furst mentions the sculpture of Potrero Nuevo, which supposedly represents the coupling of a jaguar and a human being, but he does not use it for his interpretation. Finally, when it refers to the Mesoamerican belief, the author avoids talking about the symbolism of the jaguar in post-classic era, and merely mentions certain stories that, out of context, seem to support his hypothesis.86

Köhler87 rightly points out that the Olmecs anthrop zoomorphic figures are not limited to representations of men-jaguars, and identifies features of reptiles and birds in the “hybrid” sculpture. He rejects the hypothesis of images as representations of the Olmec as “sons of the jaguar, and the interpretation of such figures as “gods.” He thinks that the majority of such images appears on personal objects that constitute status symbols, and proposes that such motives might be emblems of political power constructed from the notion of double-nahualli. Therefore, that, for him, the man-jaguar does not represent the shamans in transformation, but the fact of being human and jaguar at once. Meanwhile, hybrid figures that contain traces of various animal species represent the multiple nanahualtin an individual aligned around a main nahualli. We may object that the representations described by Köhler show no resemblance to the double known for the post-classic era and nor with those described by the Florentino Codex. In particular, we noted that at least among the Aztecs, when they represent the different nanahualtin of one character, they do not mix their characteristics. Because Maya iconography associated with the glyph “way” show anthrop zoomorphic and various contemporary Mesoamerican groups believe in double monsters, it is possible that the “hybrid” sculptures represent nanahualtin, but this proposal has yet to be proved.

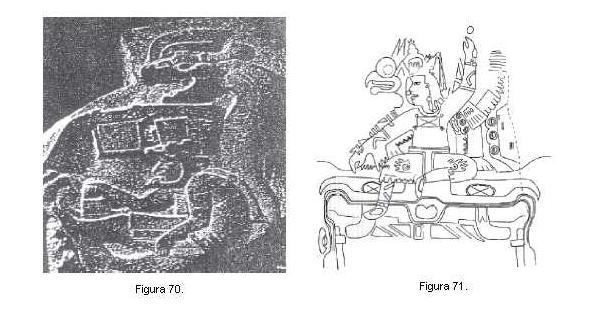

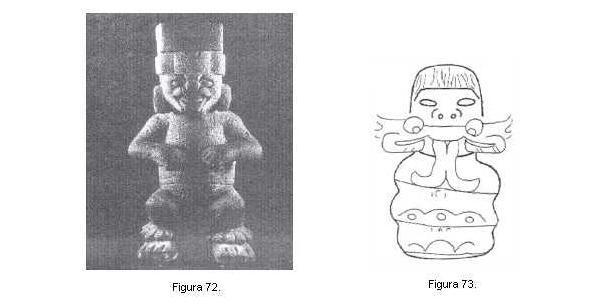

However, there are Olmec plastic manifestations much more explicit than the sculptures mentioned. For example, at the Monument 19 from La Venta we can see a seated figure with a headdress shaped like a snakehead, accompanied by a large bell that goes all the way down and than stands behind him (Fig. 70). A painting of the cave of Oxtotitlan represents an individual sitting on a throne, behind which an eagle appears in an almost identical position — as if it was his shadow (fig. 71). These are similar representations to those of the jaguar- and eagle-men of Cacaxtla and are equivalent to type C of our classification. We can also quote a statuette of Tuxtla Chico that portrays the image of a character dressed in jaguar comparable to the image of Macuil

Ocelotl of the Florentino Codex (fig. 72).88 This way of wearing the jaguar skin opposes to the one presented in the Atlihuayan statuette, where is clear that the feline’s skin is used as a layer. Finally, we mention a serpentine figure with a human head and face of a reptilian on the face (Fig. 73). In this last image, the fact of being human and snake at a time is presented in the same way that the image of Cihuacoatl of the Florentine Codex. It is worth mentioning that similar representations were not found outside the Olmec influence, so we can assume that the notion of nahualli was absent in the religious thought of other cultural complexes of the time -like Capacha Opeño and Cupícuaro-, or representation systems differ significantly from that observed in central Mesoamerica in later periods.

Conclusion

With some notable exceptions, in most cases the identification of a nahualli not associated with a character is extremely difficult. Nor have we been able to find indicators that allow us to identify men nahualli in the absence of their doubles. That is why building this classification have not been used more than character images accompanied by their nanahualtin.

There are no fixed rules about how a nahualli should be represented, but a series of more or less loose conventions that allow the identification of a double, admitting the existence of a large number of variants. With support from descriptions given in ancient sources, we have identified three main types of representation: a) characters that carry his nahualli -sometimes represented by simple head- on back. b) Images in which the anthropomorphous seem to emerge from his double. In most cases, the head of the human seems to come out of the open snout of his nahualli. We find similar representations between the Mixtec, the huastecos and the Postclassic Maya. We also see it in Tula, Chichen Itza and Cacaxtla. Comparable images also appear in the maya area, El Tajín, Teotihuacan, the Zapotec in the classic period and between the pre-classical Olmecs. c) Representations of doubles that appear behind the characters to which they are associated. We also find images in which the nahualli is presented in place of the head or foot of the character (type d) between the Aztecs and Maya Classic, and representations in which the nahualli stands in front of the character, between huastecos and Aztecs.

The different ways to represent the double can be grouped into two major categories: those in which the nahualli appears next to the character it is associated to and those with the character either carrying or wearing his double. Since the nahualli was regarded as a sort of cover, clothing or costume, it is possible that what the sources call the transformation was thought as the fact of wearing or carrying the double and that these images represent the transformation.

Thus, we would have a number of representations of men associated with animals, similar to the types of nahualli representations used in the Postclassic, that appear consistently in different times and regions. Thus, we might assume that concepts like belief in the double must have existed at least since the Olmec period. Unfortunately, we do not know in depth the Mesoamerican prehistory as to determine whether nahualli elements existed in the religious thought of this period.

Moreover, deciphering the Mayan glyph way -drawn as an ajaw glyph half covered by a jaguar skin- allows us to see that a number of images of doubles -not associated with characters- exist, which could hardly have been identified in the absence the mentioned sign. Among the Olmec are anthrop zoomorphic figures and hybrid creatures whose significance is still unknown, leaving us with a glimpse of the enormous amount of nanahualtin representations that might have existed and that we are not able to identify.

We can thus conclude that while this work itself does not provide a wealth of information on the complex conceptions of the nahualli, identification of such item in plastic registration opens the doors to the study of the nahualismo at times for which we do not have written documents. Therefore, I think that the relevance of the article is justified to the extent it exceeds other researchers because it is not a finished work but an invitation to address an issue that until now had scarcely been addressed.

Bibliografía

Aguirre Beltrán, Gonzalo, Medicina y magia. El proceso de aculturación en la estructura colonial, México, INI, 1992, [1963].

____________, El proceso de aculturación y el cambio sociocultural en México, México, FCE/INI/Gobierno del Estado de Veracruz, 1992 [1957].

____________, “Nagualismo y complejos afines en el México colonial” en Aguirre Beltrán, Gonzalo, Medicina y magia, México, INI, 1963.

Alvarado, Francisco, Vocabulario en lengua mixteca, Wigberto Jiménez Moreno (ed.), México, INI/INAH/SEP, 1962 [1593].

Alvarado Solís, Neyra Patricia, “Lier la vie et défaire la mort. Le système rituel des mexicaneros”, tesis doctoral, Université de Paris X, Nanterre, 2001.

Alvarado, Tezozomoc, Crónica Mexicana, Manuel Orozco y Berra (ed.), México, Leyenda, 1980 [1944].

Antigüedades de México. Manuscrits mexicains compilés par Lord Kingsborough, José Corona Núñez (ed.), 4 vols., México, Secretaría de Hacienda y Crédito Público, 1964-1967.

Arlegui, José, Crónica de la provincia de NSPS San Francisco Zacatecas, México, 1851 [1737].

Arnauld, Charlotte y Danièle Dehouve, “Poder y magia en los pueblos indios de México y Guatemala”, en Tiempos de América, núm. 1, Castellón, Fundacio Caixa Castello, 1997, pp. 25-44.

Báez-Jorge, Félix, Entre los naguales y los santos, Xalapa, Universidad Veracruzana, 1998.

Báez-Jorge, Félix y Arturo Gómez Martínez, “Tlacatecolotl, señor del bien y del mal (dualidad en la cosmovisión de los nahuas de Chicontepec)”, en Johanna Broda y Félix Báez-Jorge (eds.), Cosmovisión, ritual e identidad de los pueblos indígenas de México, México, FCE (Biblioteca Mexicana), 2001, pp. 391-451.

Boremanse, Didier, Contes et mythologie des Indiens Lacandons. Contribution à l’étude de la tradition orale maya, París, L’Harmattan, 1986.

Bright, William, “Un vocabulario náhuatl del Estado de Tlaxcala”, en Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, vol. VII, México, IIH-UNAM, 1967, pp. 233-254.

Broda, Johanna y Félix Báez-Jorge (eds.), Cosmovisión, ritual e identidad de los pueblos indígenas de México, México, FCE (Biblioteca Mexicana), 2001.

Buchler, Ira, “Nagualism: A structural sketch of tales from a mexican village”, en Anthropology, vol. IV, núm. 2, Nueva York, State University of New York, 1980, pp. 1-14.

Calnek, Edward, Highland Chiapas before the Spanish conquest, Provo, UTAH, New World Archaeological Foundation-Brigham Young University, 1988.

Campos, Julieta, La herencia obstinada. Análisis de cuentos nahuas, México, FCE, 1982.

Carmack, Robert y James Mundloch (eds.), El Título de Yax y otros documentos quichés de Totonicapan, Guatemala, México, UNAM, 1989.

Chilam Balam de Chumayel, The book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. Heaven born Merida and its destiny, Munro S. Edmonson (trad.), Austin, Uni versity of Texas Press, 1986.

Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin [Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñón], Relaciones originales de Chalco Amaquemecan, S. Rendón (trad.), México, FCE, 1965.

Ciudad Real, fray Antonio de, Calepino de Motul: Diccionario maya-español, Ramón Arzápalo Marín (ed.), 3 vols., México, Instituto de Inves ti gaciones An tropológicas-UNAM, 1995.

Codex Azcatitlan, Michel Graulich (revisor), Robert Barlow (comentador), Leonardo López Luján y Dominique Michelet (trads.), París, BNF-Société d’Américanistes, 1995.

Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, Ferdinand Anders, Maarten Jansen y Luis Reyes (eds.), Graz/México, Akademische Druk-und Verlagsanstalt/FCE, 1994.

Codex Telleriano-Remensis: ritual, divination and history in a pictorial aztec manuscript, Eloise Quiñones Keber (ed.), Austin, University of Texas Press, 1995.

Codex Vaticanus 3773 o Codex Vaticanus B, Ferdinand Anders (ed.), Graz/México/Madrid, Akademische Druk-und Verlagsanstalt/Sociedad Estatal Quinto Cen te nario/FCE, 1993.

Codex Vaticanus 3773 o Codex Vaticanus B., Ferdinand Anders, Maarten Jan sen y Luis Reyes (eds.), Graz/México, Akademische Druk-und Verlag sanstalt/FCE, 1993.

Códice Alfonso Caso: La vida de 8 Venado (Colombino Becker I), México, Pa tronato Indígena, 1996.

“Códice Bodley”, 1964, en Antigüedades de México (1964-1967), vol. II, pp. 31-75.

Códice Borbónico, Francisco del Paso y Troncoso (ed.), México, Siglo XXI, 1988.

Códice Borbónico. El libro del Ciuacóatl: Homenaje para el fuego nuevo, Ferdinand Anders, Maarten Jensen y Luis Reyes, Graz/México, Akademische Druk-und Verlagsanstalt/FCE, 1991.

Códice Borgia: Los templos del cielo y de la oscuridad. Oráculos y liturgia, Ferdinand Anders, Maarten Jensen y Luis Reyes, Graz/México, Akademische Druk-und Verlagsanstalt/FCE, 1993.

Códice Chimalpopoca. Anales de Cuauhtitlan y Leyenda de los Soles, Primo Feliciano Velásquez (ed.), México, IIH-UNAM, 1945.

Códice Laud, Carlos Martínez Marín (ed.), México, INAH/SEP, 1961.

Códice Laud, Cottie A. Burland (ed.), Graz, Akademische Druk-und Verlagsanstalt, 1966.

Códice Madrid: Tro cortesiano, Roberto Escalante Hernández (ed.), Puebla, Museo Amparo, 1992.

Códice Selden, en Antigüedades de México (1964-1967), vol. II, 1964, pp. 78-99.

Codex Vaticanus 3738 o Vaticanus A., Graz, Akademische Druk-und Verlagsanstalt, 1979.

Códice Vindobonensis o Mexicanus I, en Antigüedades de México, 1967, vol. IV, 1967, pp. 51-183.

Códice Zouche-Nuttall, Ferdinand Anders, Maarten Jensen y Luis Reyes, Graz/México, Aka demische Druk-und Verlagsanstalt/FCE, 1992.

Coe, Michael, “Olmec jaguars and olmec king”, en Elizabet Benson (ed.), The cult of the feline: A conference in pre-Columbian iconography, Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Trustees for Harvard University, 1972, pp. 1-12.

Cordier, Eric, “Varou, le loup-garou en Normandie”, en Terres des signes, núm. 2, Paris, 1995.

____________, “Tentative d’interprétation de la dévalorisation des animaux domestiques dans les lexiques de patois normand et français”, en Ethnozootechnie, núm.71, Paris, 2003, pp. 121-132.

Cortez y Larraz, Pedro, Descripción geográfica moral de la diócesis de Goathemala, 2 vols., Guatemala, Biblioteca Goathemala de la Sociedad de Geografía e Historia de Guatemala, 1958.

Dirección General de Culturas Populares, La plaga de los chapulines y otros cuentos nahua, México, Cuadernos de Trabajo Acayucan, núm. 4, 1982, pp. 14-39.

Enzo, Serge, Metamorfosis de lo sagrado y de lo profano. Narrativa náhuatl de la Sierra Norte de Puebla, México, INAH (Divulgación), 1990.

Fábregas Puig, Andrés, “El nahualismo y su expresión en la región de Chalco-Amecameca”, tesis para obtener el grado de Maestro en Ciencias Antropológicas, ENAH/INAH/SEP, México, 1969.

Figuerola Pojul, Helios, “El cuerpo y sus entes en Cancuc, Chiapas”, en Trace, núm. 38, México, Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Cen tro ame ricanos, 2000, pp. 13-24.

Foster, George, “Nagualism in Mexico and Guatemala”, en Acta Americana, Revista de la Sociedad Interamericana de Antropología y Geografía, vol. II, núm. 1-2, Los Ángeles-México, 1944, pp. 84-103.

Freidel, David, Linda Schele y Joy Parker, Maya cosmos: Three thousand years on the shaman’s path, Nueva York, William Morrow and Company, 1993.

Fuentes y Guzmán, Francisco Antonio, Historia de Guatemala. O Recordación Florida. D. Justo Zaragoza (ed.), t. I, Luis Navarro Editor, Madrid, 1882.

Furst, Peter, “The olmec were-jaguar motif in the light of ethnographic reality”, en Elizabet Benson (ed.), Dumbarton Oaks Conference on the Olmec, Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Trustees for Harvard University, 1967, pp. 143-178.

____________, “Shamanism, transformation and olmec art”, en Michael Coe (coord.), The olmec world: Ritual and rulership, Princeton, The Museum of Princeton University, Harry N. Abrams, 1996, pp. 69-80.

García, Gregorio, Origen de los indios en el Nuevo Mundo e Indias Occidentales, Madrid, Imprenta de Francisco Martínez Abad, 1729.

García de León, Antonio, “El universo de lo sobrenatural entre los nahuas de Pajapan, Veracruz”, en Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, vol. VIII, México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas-UNAM, 1969, pp.279-312.

Garibay, Ángel María (comp.), Veinte himnos sacros de los nahuas, México, UNAM, Seminario de Cultura Náhuatl, 1958.

Guiteras Holmes, Calixta, Perils of the soul. The world view of a tzotzil Indian, Nueva York, The Free Press of Glencoe, Crowell/Collier Publishing Company, 1961.

Gossen H. Gary, “Animal souls and human destiny in Chamula”, en Man, vol. 10, núm. 1, Londres, Royal Anthropology Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 1975, pp. 448-461.

Graulich, Michel, “Dualities in Cacaxtla”, en Rudolf van Zantwijk, Rob de Ridder, Edwin Braakhuis (eds.), Mesoamerican dualism. 46th Internationa Congres of Americanists, Amsterdam 1988, Utrech, RUU-ISOR, 1990, pp. 94-118.

____________, “El rey solar en Mesoamérica”, en Arqueología Mexicana, vol. VI, núm. 32, México, INAH/Raíces, 1998, pp. 14-49.

Greimas Algridas, Julien y Joseph Courtes, Dictionnaire raisonné de la théorie du langage, París, Librairie Hachette, 1986.

Grove, David, “Olmec felines in highland central Mexico”, en Elizabeth Benson (ed.), The cult of the feline: A conference in pre-Columbian iconography, Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collections, Trustees for Harvard University, 1972, pp. 153.

Grube, Nikolai y Nahm Werner, “A census of Xibalba: a complete inventory of way characters on maya ceramics”, en The maya vase book. A corpus of rollout photograph of vases, vol. IV, New York, Kerr Asociates, 1994, pp. 686-715.

Hamayon, Roberte, “Pour en finir avec la ‘transe’ et l extase dans l’étude du chamanisme”, en Études mongoles et sibériennes, núm. 26, Maison de l’Archéologie et l’Ethnologie, Paris X, Nanterre, 1995.

Hermitte, Esther, “El concepto del nahual entre los mayas de Pinola”, en Norman A. McQuown y Julian Pitt-Rivers (comps.). Ensayos de Antropología en la zona central de Chiapas, México, INI, 1970.

“Historia quiché de don Juan de Torres”, en Adrián Recinos (ed.), Crónicas indígenas de Guatemala, Guatemala, Editorial Universitaria, 1957.

“Historia de los xpansay de Tecpan, Guatemala”, en Adrián Recinos (ed.), Crónicas indígenas de Guatemala, Guatemala, Editorial Universitaria, 1957.

Houston, Stephen y Stuart David, “The Way glyph: Evidence for ‘co-essences’ among the Classic Maya”, en Stephen Houston, David Stuart y Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos (eds.), The decipherment of ancient Maya writing, Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Kettunen Harri J. y Helmke Chistophe G.B., Introduction to maya hieroglyphs: Notebook for the 7th European Maya Conference, Londres, Communications in Print/University College London/British Museum, 2002.

Köhler Ulrich, “Olmeken und Jaguare. Zur Deutung von Mischwesen in der präklassischen Kunst Mesoamerikas”, en Anthropos, vol. LXXX, núm. 4-6, Anthropos Institut, Verlag Paulusverlag Fribourg, 1985, pp. 15-52.

Krickeberg, Walter, “Les religions des peuples civilisés de Méso-Amérique”, en W. Krickeberg, Hermann Timborn, Werner Müller y Otto Zerries (eds.) y L. Jospin (trad.), Les religions amérindiennes, Paris, Payot, 1962, pp. 15-119.

Lipp, Frank J., The Mixe of Oaxaca. Religion, ritual and healing, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1991.

López-Austin, Alfredo, Cuerpo humano e ideología. Las concepciones de los antiguos nahuas, México, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas/UNAM, 1989-1996.

Marcus, Joice y Kent Flannery, “Cultural evolution in Oaxaca. The origins of zapotec and mixteca civilization”, en Richard E. W. Adams y Murdoc J. Mc Cleod (eds.), The Cambridge history of native peoples of the Americas. vol. II. Mesoamerica part I., Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 358-406.

Martínez González, Roberto, “Crítica al modelo neuropsicológico. Un abuso de los conceptos trance, éxtasis y chamanismo, a propósito del arte rupestre”, en Cuicuilco vol. X, núm. 29, México, 2003.

____________, “Le nahualli: homme-dieu et double animal au Mexique”, en Anthropozoologica, vol. XXXIX, núm. 1, Publications Scientifiques du Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 2004, pp. 371-381.

Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo, El calendario azteca y otros monumentos solares, México, INAH, 2004.

Molina, Alonso de, Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, México, Porrúa, 2001 [1571].

Münch Galindo, Guido, Etnología del istmo veracruzano, México, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM, 1994.

Núñez de la Vega, Francisco, Constituciones diocesanas del obispado de Chiapa, María del Carmen León Cazares y Mario Humberto Ruz (eds.), México, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas/Centro de Estudios Mayas/UNAM, 1988.

Oakes Maud, The two crosses of Todos Santos. Survivals of mayan religious ritual, New York, Pantheon Books, Bollingen Series XXVII, 1951.

Olivier, Guilhem, “Espace, guerre et prospérité dans l’ancien Mexique Central: Les dieux marchands à l’époque Postclassique”, en Journal de la Société d’Américanistes, t. LXXXV, CNRS-Musée de l’Homme, Paris, 1999, pp. 67-91.

Pitarch, Ramón Pedro, “Almas y cuerpo en una tradición tzeltal”, en Archives de sciences sociales des religions, núm. 112, CNRS/EHESS, Paris, 2000, pp. 31-48.

Pitt-Rivers Julian, “Spirit power in Central America. The naguals of Chiapas”, en Mary Douglas (ed.) Witchcraft, confessions and accusations, Nueva York/Londres, Tavistock Publications, 1970, pp. 183-206.

Popol Vuh, The Book of the Counsel: The Popol Vuh of the Quiché Maya of Guatemala, Edmonson, Munro S. (ed.), New Orleans, Tulane University, Middle American Research Institute, Publication 35, 1971.

Pury, Sybille de y Marc Thouvenot, Dictionnaire nahuatl-espagnol, a partir du BNF núm. 362, París, Editions Sup-Infor, 2001.

Recinos, Adrián (ed.), Crónicas indígenas de Guatemala, Guatemala, Editorial Universitaria, 1957.

Reilly III, Kent, “Art, ritual and rulership in the olmec world”, en Michael Coe (coord.), The olmec world: Ritual and rulership, Princeton, The Museum of the Princeton University/Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Robe, Stanley L., Mexican tales and leyends from Veracruz, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1971.

Robicsek, Francis, “Of olmec babies and were-jaguars”, en Mexicon, vol. V, núm. 1, Berlín, Internationale Gesellschaft für Mesoamerika-furschung, 1983.

Ruiz de Alarcón, Hernando, Treatise on the heathen superstitions and customs that today live among the Indians native to this New Spain, Richard Andrews y Ross Hassing (trads.), Norman-Londres, University of Oklahoma Press, The civilization of American Indian Series, vol. CLXIV, 1984.

Sahagún, Bernardino de, Florentine Codex. General history of the things of New Spain, Arthur J. O. Anderson, Charles E. Dibble (trads.), Santa Fe, Mo no graphs of the School of American Research, 1950-1963.

____________, Augurios y abusiones. Fuentes indígenas de la cultura náhuatl, Alfredo López-Austin (comp.), México, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas-UNAM, 1969.

____________, Primeros memoriales de Tepeapulco, Thelma Sullivan (trad.), Norman, The University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Seler, Eduard, Comentarios al Códice Borgia. 3 vols., México, FCE, 1963.

Serna, Jacinto de la, “Manual de ministros de indios para el conocimiento de sus idolatrías y extirpación de ellas”, en Francisco del Paso y Troncoso (ed.), Tratado de las idolatrías, supersticiones, dioses, ritos, hechicería y otras costumbres gentílicas de las razas aborígenes de México, vol. I, México, Fuente Cultural, 1953, pp. 47-368.

Signorini, Italo y Alessandro Lupo, Los tres ejes de la vida. Almas, cuerpo, enfermedad entre los nahuas de la Sierra de Puebla, Xalapa, Universidad Veracruzana, 1989.

Taggart, James, Nahuatl myth and social structure, Austin, University of Texas Press, 1984.

Título de Totonicapán, Robert M. Carmak y James L. Mondlonch (trads.), México, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas/Centro de Estudios Mayas-UNAM, 1983.

Vázquez Dávila, Marco y Enrique Hipólito Hernández, “La cosmovisión de los chontales de Tabasco. Notas preliminares”, en América Indígena, vol. LIV, núm. 1-2, III, México, 1994, pp. 149-165.

Villa Rojas, Alfonso, “Kinship and nagualism in a Tzeltal community, southeastern Mexico”, en American Anthropologist, vol. XLIX, American Anthropological Association, Wisconsin, 1947, pp. 578-587.

____________, “El nagualismo como recurso de control social entre los grupos mayances de Chiapas, México”, en Estudios de Cultura Maya, núm. 3, México, Centro de Estudios Mayas, Instituto de Investigaciones Filológicas-UNAM, 1963, pp. 243-260.

Vogt Z. Evon, Zinacantan. A Maya community in the highlands of Chiapas, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1969.

Wicke, Charles, Olmec: An early art style of pre-Columbian Mexico, Tucson, University of Arizona Press, 1971.

Autor: Roberto Martínez González, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas-UNAM. Translation by Carmen Martí Cotarelo. Agradezco al Programa de Becas Posdoctorales de la UNAM y al Programa de Becas-Crédito del Conacyt por el apoyo económico que hizo possible la realización de este studio. Asimismo, doy gracias al Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas por el apoyo logístico y a mis maestros Michael Graulich y Alfredo López Austin por sus sabias enseñanzas y consejos.

- Roberto Martínez , “Le nahualli: homme-dieu et double animal au Mexique”, in Anthropozoologica, vol. XXXIX, nbr. 1, 2004, 373-374. [↩]

- An example of this are the words like nahualtia. Nicno, “to hide or cover with something”, and imanahual, “Cradlle Baby’s blankett” (Alonso de Molina, Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana y mexicana y castellana, 2001, 63v, 38r) —from the nahua or nahual root — is used in the old dictionaries to express something related to “coverage” or “coating”. Following this same vein, today we find that, in the Nahuatl of Tlaxcala, the term nahual is used to translate the words “coat or layer”. See William Bright”, “Un vocabulario náhuatl del estado de Tlaxcala”, en Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, vol. VII, 1967, 243. While the Nahua of the Chimalhuacan región use that Word to call the “masked dancers”, see Andrés Fábregas Puig, “El nagualismo y su expresión en la región de Chalco-Amecameca”, tesis, ENAH, 1969, 101. [↩]

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex. General history of the Things of New Spain [CF], 1950, I, 1-2; XII, 50 explains that the fire snake and the hummingbird where nahualis of Huitzilopochtli. Ixcozauhqui. Who also had the fire snake as the nahualli Ángel María Garibay (comp.), “Veinte himnos sacros de los nahuas”, 1958,126-127; Thelma Sullivan (trad.), Primeros memoriales de Tepeapulco, 1997, 94 and Painal (CF, op. cit., I, p. 2, II, 161) shared with Huitzilopochtli the double of the hummingbird. Coyotl inahual, patron of the feather craftsmen, had a coyote as his nahualli, Macuil Ocelotl had a jaguar and Macuil Tochtli had a rabbit (CF, IX, 83-84). For Tezcatlipoca, three different nahuallis are mentioned; The giant, the ash package-men and the night axe (Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Augurios y abusiones, 1969, 50-51, 52-53, 58-59). In addition, it mentions that the tetlanonochili “procuress” had as nahual a tzitzimitl (CF, X, 57, X, 32), that the nahualli-men of noble origin had as a double beast (tecuani), to their colleagues of humble origin corresponded a beetle, a dog or a turkey. [↩]

- For example, Archbishop Cortez and Larraz (Descripción geográfica moral de la diócesis de Goathemala, 1958. vol. I, p. 103) states on indigenous last-names or nicknames: “The ones that have one, are completely inconsistent. Brothers have different names, neither the child has the same as his father. Usually such nicknames, the same as their language, use the names of various animals. For example Peter horse, Juan of the deer, Antonio of the dog, etc.. Those are not only their names, but also expresses their nahuales or protectors … “ [↩]

- We find the collective believe in nanahualtin, between the nahuas of Central Mexico (in this case attributed to the xochtecas, olmecas and quiyahuiztecas). As to the mayas-yucatecos, quichés and cakchiqueles of Guatemala (see Domingo Francisco de San Antón Muñón, Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, Relaciones originales de Chalco Amaquemecan, 1965, 88; “Historia Quiché de Don Juan de Torres”, en Adrián Recinos (ed.), Crónicas indígenas de Guatemala, 1957, 25, 45; Chilam Balam de Chumayel, 1986, 90; Título de Totonicapan: 1983, 194, 26r). [↩]

- See Jacinto de la Serna, “Manual de ministros de indios para el conocimiento de sus idolatrías y extirpación de ellas”, in Francisco del Paso y Troncoso (ed.), Tratado de las idolatrías, supersticiones, dioses, ritos, hechicerías y otras costumbres gentílicas de las razas aborígenes de México, 1953, 204. Francisco Núñez de la Vega, Constituciones diocesanas del obispado de Chiapa, 1988, 757. [↩]

- For more details on the nahualli, and the form adopted in the transformation see Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (op. cit., 1969, 50-51), el Códice Florentino (1950, X, 31, 32), Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón (Treatise on the heathen superstition and customs that today live among the Indians native to this New Spain, 1984, 48), Antonio de Ciudad Real (Calepino de Motul: Diccionario maya español, 1995, 746), Francisco Núñez de la Vega (op. cit., 1988, 757), Francisco Antonio Fuentes y Guzmán (Historia de Guatemala. O recordación fl orida, 1882 II, 45) y José Arlegui (Crónica de la provincia de NSPS San Francisco Zacatecas, 1851, 145). For more information about nahualismo in general, see George Foster (“Nagualism in Mexico and Guatemala”, in Acta Americana, vol. II, núm. 1-2, 1944, 84- 103), Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán (Medicina y magia. El proceso de aculturación y el curanderismo en México, 1955; Nagualismo y complejos afines en el México colonial, 1978), Calixta Guiteras Holmes (Perils of the soul. The world view of a tzotzil indian, 1961), Alfonso Villa Rojas (“Kinship and nagualism in a tzeltal community, southeastern Mexico”, in American Anthropologist, vol. XLIX, 1947, 578-587), Evon Vogt (Zi nacantan. A maya community in the highlands of Chiapas, 1969), Esther Hermitte (“El concepto del nagual entre los mayas de Pinola”, in Norman A. McQuown and Julian Pitt-Rivers (comps.), (Ensayos de Antropología en la zona central de Chiapas, 1970), H. Gary Gossen (“Animal souls and human destiny in Chamula”, in Man, vol. 10, núm. 1, 1975, 448-461), Julian Pitt-Rivers (“Spirit power in Central America. The naguals of Chiapas”, en Douglas (ed.), Witchcraft confessions and accusations, 1970, 183-206), Alfredo López Austin (Cuerpo humano e ideología. Las concepciones de los antiguos nahuas, 1989), Italo Signorini y Alessandro Lu po, (Los tres ejes de la vida. Almas, cuerpo, enfermedad entre los nahuaas de la Sierra de Pue bla, 1989), Ramón Pedro Pitarch “Almas y cuerpo en una tradición tzeltal”, in Archives des sciences sociales des religions, núm 112, 2000, 31-48), Helios Figuerola Pojul (“El cuerpo y sus entes en Cancuc, Chiapas”, in Trace, núm 38, 2000, 13-24), Charlotte Arnauld y Da niéle Dehouve (“Poder y magia en los pueblos indios de México y Guatemala”, in Tiempos de América, núm. 1, 1997, 25-44), Félix Báez-Jorge (Entre los naguales y los santos, 1998) and Roberto Martínez González (“Le nahualli: homme-dieu et doublé animal au Mexique”, in Anthropozoologica, vol. XXXIX, núm. 1, 2004, 371-381). [↩]

- What for Julien Greimas and Joseph Courtes (Dictionnaire raisoné de la théorie du langage, 1986, 339) is called semiosis, that means, “The operation that restores a relation of reciprocal presupposition between the form of the expression and that of the content.”. [↩]

- See Alfredo López Austin, op. cit. A component of mind, determined by the sign corresponding to the calendar date of birth of the character, which is closely tied to the destiny and character of the individual. [↩]

- CF, X, 1950, 47-48. [↩]

- Robert Carmack and James Mundloch (eds.), “Título de Yax”, in El título de Yax y otros documentos quichés de Totonicapan, Guatemala, 1989. [↩]

- Walter Krickeberg (“Les religions des peuples de MésoAmérique civilis” in Les religions amérindinnes, 1962, 59) had already stated some of the fundamental principles of plastic representation of nahualli. “On Mexican representations, is not unusual to find that the god or the man is carrying the head of his double over his own head and appears at the bottom of the nose or completely enveloped by the skin […]. It is also the idea of alter ego associated of Toltec representation [is wrong, is Aztec] Ce-Acatl-Quetzalcoatl, in his double, the feathered serpent, stands behind him like a giant shadow with majestic undulations. [↩]

- Ángel María Garibay, op. cit., 1958, 126-127; Thelma Sullivan (trad.), op. cit., 1997, 94. [↩]

- “Yxiuhcoanahual: yn quimamaticac”, “he carries his nahualli-snake of fire on his back”. [↩]

- CF, IX,. 1 and 13 [↩]

- Francisco del Paso y Troncoso (ed.), Códice Borbónico, 1988, 22. [↩]

- Ferdinand Anders, Maarten Jensen and Luis Reyes (comittee de inv.), Códice Borgia: los templos del cielo y de la oscuridad. Oráculos y liturgia, 1993, 46. [↩]

- Codex Vaticanus 3738 o Vaticanus A, 1979, fol. 6. [↩]

- CF, IX, 83. [↩]

- Ibidem, 84. [↩]

- The text in náhuatl says: in Macuil Ocelotl onac ticaca in naoal in tecuani itzontecon […] Zan ie no iuhqui in Macuil Tochtli, no onacticac in inaoal, in iuhqui tochin itzotecon. [↩]

- CF, XII, 50 [↩]

- The text in náhuatl says: Yoan teuxtli yoa icpac conquetza iutzitzilnaoal. [↩]

- Códice Azcatitlan, 1995, 1v., 2v., 4v., 6r., 8r., 12r [↩]

- Ibidem, 10v. [↩]

- Códice Borgia…, op.cit., 65. [↩]

- Códice Telleriano Remensis: ritual, divination and history in a pictoral aztec manuscript, 1995, 13, 48. [↩]

- Ibidem, 24. [↩]

- In most of the cases, Itztapaltotec —by the way, an aspect of Xipe Totec— appears wearing a kind of helmet in the shape of an obsidian knife with a human shape (CódiceBorbónico, 1991, 20; Códice Telleriano-Remensis, 1995, 50); as in all mentioned cases, the face of the deity is coming out of the open mouth of the knife (fig. 21). ¿Is it possible, in this case, that the obsidian knife was his nahualli? [↩]

- CF, IX, 71. [↩]

- Códice Borgia…, op. cit., 38. [↩]

- Códice Borbónico, op. cit., 3, 17. [↩]

- This is the same kind of representations that belong the images of the serpents of fire of whose jaws emerge in the Aztec Calendar the faces of Huitzilopochtli and Xiuhtecuhtli. (see Eduardo Matos, El Calendario azteca y otros monumentos solares, 2004, 72). [↩]

- Codex Vaticanus 3773 or Codex Vaticanus B, 1993, f. 48. [↩]

- Códice Laud, 1961, 62 [↩]

- Ibidem, 76; Codex Féjerváry-Mayer, 1994, f. 17, Codex Vaticanus 3773 o Codex Vaticanus B, 1972, 22. [↩]

- Códice Borbónico, op. cit., 1988, 17. [↩]

- Seemingly, the date 7-Caña does not show the date of birth or death of the character, but the date when a river called Acuecuexatl was diverted (Códice Chimalpopoca, 1945, 58). [↩]

- Michel Graulich, personal communication. [↩]

- Michel Graulich, “El rey solar en Mesoamérica”, in Arqueología Mexicana, vol. VI, Nbr. 32, 1998, 18. [↩]

- Codex Féjérvary-Mayer, op. cit., 1994, f. 10. [↩]

- Guilhem Olivier, “Espace, guerre et prospérité dans l’áncien Mexique Central: les dieux marchands á l’époque Postclassique”, en Journal de la Société d’Américanistes, t. LXXXV, 1999, 70-71; CF, I, 64. [↩]

- The fact that Eduard Seler (Comentarios al Codice Borgia, 1963, II, 133) identifies this representation with Tezcatlipoca implies no contradiction with the position of Olivier. It is highly likely that, as noted by the latter author, Axomocuil is nothing more than an avatar of Tezcatlipoca. The same codex (ibid., fol. 8) shows a goddess merchant carrying the head of a coral snake in the same place. [↩]

- Códice Laud, 1966, 2, 15. [↩]

- Codex Vaticanus…, op. cit., 1993, f. 48. [↩]

- CF, X, pl. 74. [↩]

- CF, XII, pl. 45. [↩]

- Behind the character or on his back [↩]

- Where the individual carries the head of his nahualli or vice versa and when the character appears as emerging from the mouth of his double. One of the most interesting types of representation in this second class is one in which the character appears to be wearing the skin of his nahualli. [↩]

- Códice Borbónico, op. cit., 1991, 22. [↩]

- Códice Borgia…, op. cit., p. 44. [↩]

- Tezozomoc Alvarado, Crónica mexicana, 1980, 265. [↩]

- A term used to refer to the nahualli-man (CF, X, 31). [↩]

- CF, XI, 3. [↩]

- That means, adding the name of the animal. In this case deer (mazatl ) or a rabbit (tochtli), with the suffix tilia. [↩]

- For example, The Legend of the Suns (Codex Chimalpopoca, op.cit.., P. 121) expresses the transformation of Quetzalcoatl in ant as “eic ticzcatl mocuep in Quetzalcoatl”, Annals of Cuauhtitlan (Codex Chimalpopoca, op. Cit. ) says about women who became two-headed deer “in mamaz cactus in omocuepque cihua e” and the informants of Sahagún (op. cit., 1969, p. 50) state as follows the fact that the giant was regarded as the transformation of Tezcatlipoca “inecuepaliz in tlacateculotl Tezcatlipoca. [↩]

- Such is the case of a mention in the Augurios y abusiones de Sahagún (op. cit., 1969, 60) that is said about Tezcatlipoca: “Tezcatlipoca Quitoaya ca miecpa quimonahualtiaya in coyotl, meaning” they said Tezcatlipoca disguised [hid or covered] as a Coyote. [↩]

- Ixcuepa, translated by Molina as “turn the inside to outside,” clearly denotes the rotation. The sense of transformation appears in Manuscript 362 of the BNF (2001, 21), which translates the phrase “cueponi xotla” for “open flowers or sprout”. Nowadays this word is also used with the sense of “translate”. Today many Mesoamerican communities believe in “rituals” of transformation involving rotational movements. (see Neyra Patricia Alvarado Solís, “Lier la vie et défaire la mort. Le systéme rituel des mexicaneros”, tesis doctoral, 2001, 320; Sergre Enzo, Metamorfosis de lo sagrado y de lo profano.Narrativa náhuatl de la Sierra Norte de Puebla, 1990, 349; Ira Buchler, “Nagualism: A structural sketch of tales from a mexican village”, in Anthropology, vol. IV, núm 2, 1980, 7; Frank J. Lipp, The mixe of Oaxaca. Religion, ritual and healing, 1991, 161). Thus, we can note that there is a metonymic relationship between the term for processing, cuepa “to transform” and the rolling action. Could be a pun on “make” and “becoming animal” that had inspired the invention of “ritual”. One element that could strengthen this hypothesis is the fact that one of the informants of Stanley L. Robe (Mexican Tales and Legends from Veracruz, 1971, 142) used precisely the manchicuepa word to describe the movement producing transformation. According to De Pury (2003, pers. Com.), It is possible that the term manchicuepa is a deformation of maixcuepa “que torne mi cara!”. [↩]

- CF, IV, 41-43. [↩]

- Andrés Fábregas, op. cit., 1969, 102; Julieta Campos, La herencia obstinada. Análisis de cuentos nahuas, 1982, 188; Didier Boremanse, Contes et mythologie des Indiens Lacandons Contribution á l’étude de la tradition orale maya, 1986, 127; Sergre Enzo, op. cit., 1990, 163; James Taggart, Nahuat myth and social structure, 1984, 209-210; Antonio García de León, “El universo de lo sobrenatural entre los nahuas de Pajapan, Veracruz”, en Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, vol. VIII, 1969, 287; Guido Münch, Etnología del istmo veracruzano, 1994, 172; Marco Vázquez y Enrique Hipólito, “La cosmovisión de los chontales de Tabasco. Notas preliminares”, in América indígena, vol. LIV, núm. 1-2, III, 1994, 151; Maud Oakes, The two crosses of Todos Santos. Survival of mayan religious ritual, 1951, 171-173. [↩]

- Félix Báez-Jorge y Arturo Gómez, “Tlacatecolotl, señor del bien y del mal (dualidad en la cosmovisión de los nahuas de Chicontepec)”, in Johanna Broda y Félix Báez-Jorge (eds.), Cosmovisión, ritual e identidad de los pueblos indígenas de México, 2001, 420. [↩]

- In parallel, we find that, as Helios Pojul Figuerola, op. cit., 15, among the Tzeltal certain individuals claim that “the lab [equivalent to Nahuatl nahualli] are like our clothes, like our shirts are part of oneself.” [↩]

- Eric Cordier, “Varou, le loup-garou en Normandie”, en Terres des signes, nbr. 2, 1995, 2; “Tentative d’interprétation de la dévalorisation des animaux domestiques dans les lexiques de patois normand et français”, en Ethnozootechnie, nbr. 71, 2003, 130. [↩]

- Códice Zouche Nutall, 1992, fol. 3; Códice Vindobonensis o Mexicanus I,in Antigüedades de México, vol. IV, 1967, lam. II, V; Códice Selden (A2), in Antigüedades de México, 1964, láms. III, V, IX, XVI, XVII; Códice Bodley, 1964, lám. I . [↩]

- The existence of a pre-Hispanic Mixtec nahualism is attested by Francisco de Alvarado (Vocabulario en lengua Mixteca, 1962, 38, 122), who translates the words sanduvui tai, tai tai ñahaque and sandacu by “sorcerer who deceived them by saying that he became a lion” and “sorcerer, magician saying that he became a tiger.” Fray Gregorio Garcia (Origin of the Indians in the New World and the West Indies, 1729, 328) mentions that the eldest son of the couple became supreme tiger, and the youngets in a small animal like a winged serpent. One of the most interesting nanahualtin representations contained in the Mixteca codices is that in showing the septum piercing rite nasus Mr. 8-Venado, in the Codex Bodley (2858) (1960, 9) (fig. 48 ). In this image shows the man sitting on the hind legs of a jaguar lying on a sacrificial stone, while the corresponding Codex Becker I (Codex Alfonso Caso, 1996, 15) is king, here 4-Viento, who figures in that position. This shows once again that the nahualli serves as representative of the individual that is associated to. [↩]

- CF, X, 194, 192. [↩]

- Popol Vuh, 1971, 169; “Historia de los xpansay de Tecpan, Guatemala”, in Adrián Recinos (ed.), Crónicas indígenas de Guatemala, 1957, 123; Título de Totonicapan, 1983, 175, 8r; Francisco Núñez de la Vega aforementionedin Edward Calnek, Highland Chiapas before the Spanish conquest, 1988, 53. [↩]

- It is noteworthy that, according to Roys (Alfonso Villa Rojas, “El nagualismo como recurso de control social entre los grupos mayances de Chiapas, México”, en Estudios de Cultura Maya, núm. 3, 1963, 256), the nahualism reached Yucatan during the Katun 5 Ahau (1323 to 1342) when the Itzaes consolidated their power in the region, but this is not completely accurate, the Mayan nahualism is much older. [↩]

- Popol Vuh, 1971, 169; “Historia de los xpansay de Tecpan, Guatemala”, in Adrián Recinos (ed.), Crónicas indígenas de Guatemala, 1957, 123; Título de Totonicapan, 1983, 175, 8r; Francisco Núñez de la Vega mentioned in Edward Calnek, Highland Chiapas before the Spanish conquest, 1988, 53. [↩]

- Michel Graulich, “Dualities in Cacaxtla”, in Rudolf van Zantwijk, Rob de Ridder, Edwin Braakhuis (eds.), Mesoamerican dualism, 1990, 100. [↩]

- Michel Graulich, “Dualities in Cacaxtla”, in Rudolf van Zantwijk, Rob de Ridder, Edwin Braakhuis (eds.), Mesoamerican dualism, 1990, 100. [↩]

- Nikolai Grube y Werner Nahm, “A census of Xibalba: a complete inventory of way characters on maya ceramics”, en The maya vase book. A corpus of rollout photograph of vases, vol. IV, 1994, p. 686; Harri Kettunen y Christophe Helmke, “Introduction to maya hieroglyphs”, 2002, 75; Hoppan, personal communication. [↩]

- Stephen Houston and David Stuart, “The way glyph: evidence for ‘co-essences’ among the Classic Maya”, in Stephen Houston, David Stuart and Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos (eds.), The decipherment of ancient maya writing, 2001, 452. [↩]

- Ibidem, 455. [↩]

- Ibidem, 457. [↩]

- Nikolai Grube and Werner Nahm, op. cit., 1994 [↩]

- David Freidel, Linda Schele and Joy Parker, Maya cosmos: Three thousand years on the shaman’s path, 1993, 184. [↩]

- Sala, personal communication [↩]

- Joice Marcus and Kent Flannery, “Cultural evolution in Oaxaca. The origins of zapotec and mixteca civilization”, in The Cambridge History of native peoples of the Americas, vol. II, 2000, 390. [↩]

- Of course, if this were the case, we still have to define whether it is possible that such suit of such military groups represent nanahualtin, perhaps the sun. [↩]

- See, for example Francis Robicsek texts (“Of olmec babies and were-jaguars”, in Mexicon, vol. V, núm. 1, 1983), Michael Coe (“Olmec jaguars and olmec king”, in Elizabet Benson (ed.), The cult of the feline: a conference in pre-Columbian iconography, 1972), Charles Wicke (Olmec: An early art style of pre-Columbian Mexico, 1971) and David Grove (“Olmec felines in highland central Mexico “, in Elizabet Benson (ed.), op. cit., 1972). [↩]

- The serpentine sculptures from Dumbarton Oaks, a figure from the Fearing collection and a piece of head of the National Museum of Anthropology. In a later work, Peter Furst. (“Shamanism, transformation and olmec art”, en Michael Coe (coord.), The olmec world: Ritual and rulership, 1996, 79) regards such statues as representations of the Olmec shaman fellow spirits. [↩]

- Peter Furst, “The olmec were-jaguar motif in the light of ethnographic reality”, in Elizabet Benson (ed.), Conference on the olmec, 1967. [↩]

- Later, Peter Furst (op. cit., 1996, 70) adds that is clearly for him that the sculptor had experienced their own transformation during ecstasy. [↩]

- In his second article on the jaguar-men, the author is a little bit more cautious about the nahualism and the post-Classic symbolic systems and avoids addressing this issue. Kent Reilly (“Art, Ritual and rulership in the Olmec World,” in Michael Coe (ed.), op.cit.., 1996) also supports the hypothesis of shamanism as the main driver for Olmec artistic creations, yet he did not try to associate these events to nahualism or any other post-classical belief. [↩]

- All this without mentioning that the concept of shamanism on which rests the author is all wrong: Shamanism is a system of religious beliefs and practices that in no way can be reduced to a trance or ecstasy. (See Roberte Hamayon, “Pour en finir avec la ‘transe’ et l’éxtase dans l’étude du chamanisme”, in Études mongoles et sibériennes, núm 26, 1995 and Roberto Martínez González, “Crítica al modelo neuropsicológico. Un abuso de los conceptos trance, éxtasis y chamanismo, a propósito del arte rupestre”, in Cuicuilco, vol. X, núm. 29, 2003). [↩]

- Ulrich Köhler, “Olmeken und Jaguare. Zur Deutung von Mischwesen in der präklassischen Kunst Mesoamerikas”, in Anthropos, vol. LXXX, núm 4-6, 1985, 15-52. [↩]

- Even if the top members look like real paws of jaguar, the mask or head of jaguar let us see a human face showing out and the feet go out of the later paws of the feline. [↩]